Have you ever wondered what the difference is between free climbing and free solo climbing? Lexically speaking, the differences may only be a few syllables, but at an application level, the incorrect use of the terms could even cost lives. We have compiled the most important disciplines and styles of climbing for you and embellished them with information on their origins.

This way, you are guaranteed not to make any wrong bets and you can also score points with some information about the disciplines.

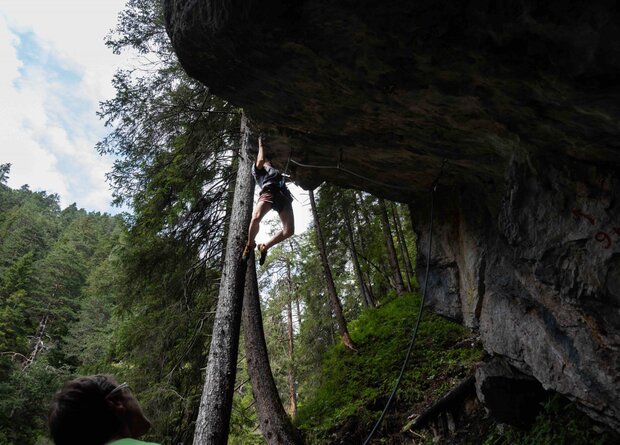

Disciplines Lead climbing

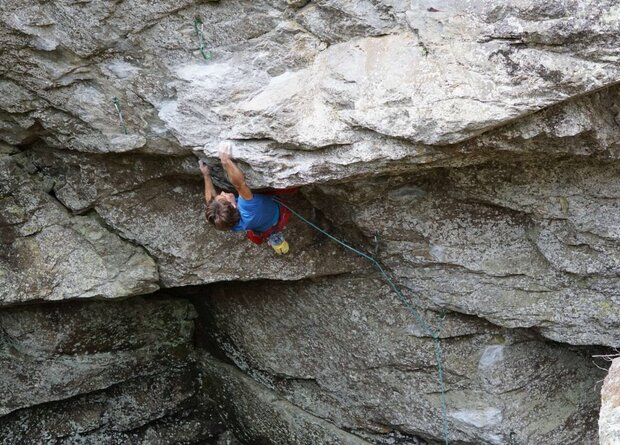

Classic lead climbing refers to climbing a route with rope protection from below with fixed intermediate protection points. The discipline sometimes requires strong nerves, as well as stamina and a lot of holding power, partly because of the need to clip in the intermediate belays, which is an additional requirement compared to toprope climbing. A lot is also demanded of the climbers in terms of tactics and technique, especially when attempting an onsight ascent. And so the Wikipedia description that it is the "physically and mentally most demanding secured ascent of a climbing route ..."proves to be true.

Historically speaking, lead climbing as we know it today experienced its boom in the USA in the late 1960s and early 1970s. American rookies were observed all over the world as they drilled routes. It was quickly recognized that you can develop much faster in this way than with clean climbing. As a result, people in Europe quickly adapted to the American model and soon started drilling routes here as well.

Lead climbing - "Jungle Book" climbing garden, Martinswand, photo: Michael Meisl

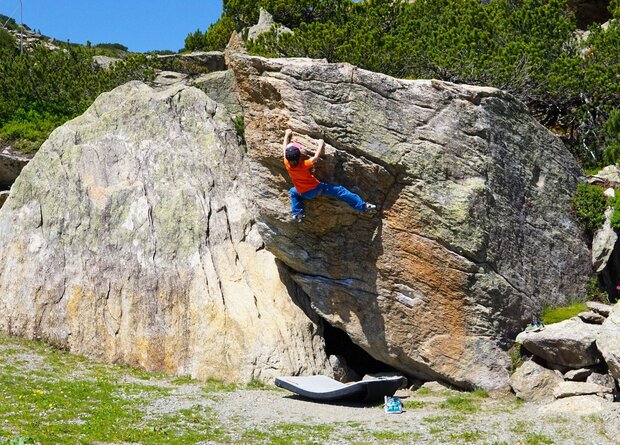

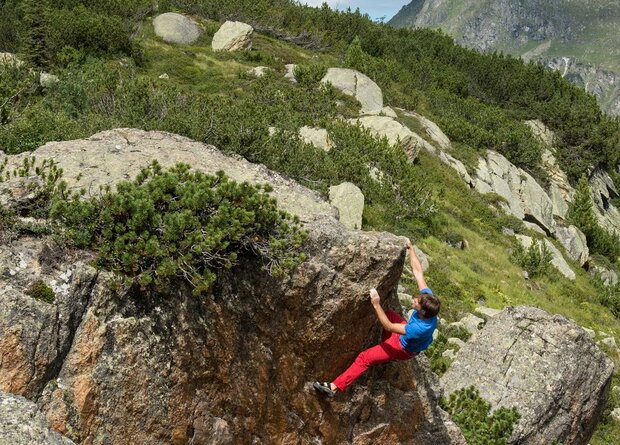

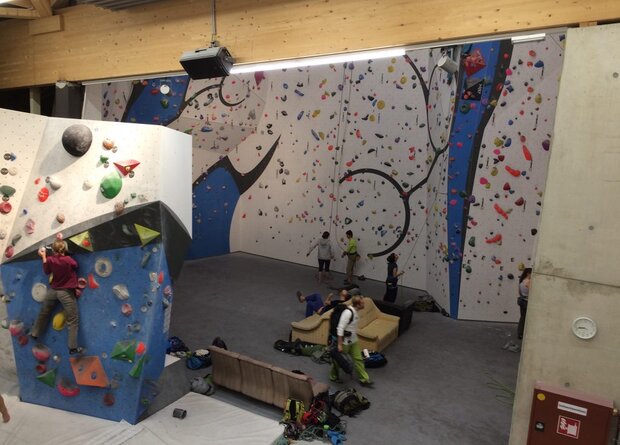

Bouldering

Probably the most popular type of climbing at the moment is bouldering. You climb up to jump height without a rope. Mats (especially indoors) or crash pads, which are brought to the rock, serve as a safety device. Real "Bleausards" even do without these and often only boulder in the forests of Fontainebleau with a small carpet, which serves to protect the rock rather than the climber. It should be said, however, that without this French climbing suppleness, bouldering without mats can be painful and dangerous.

In the birthplace of bouldering (Fontainebleau), climbing has been practiced since the 1890s. However, it was John Gill who significantly developed the discipline in the 1950s and 1960s. He developed the style of dynamic climbing and introduced magnesia to optimize friction - what a hero!

Highball climbing is a way of pushing the boundaries of bouldering. This refers to high bouldering where a fall is no longer possible without the risk of serious injury (approx. 4-5 meters). The transition to free solo climbing is fluid (from approx. 7 meters).

Bouldering in the Silvapark high above Galtür in Paznaun, photo: Simon Schöpf

Top rope

The child of parental sport climbing is called toprope. A discipline that has its raison d'être above all for beginners and children. The development of the toppa (mechanical rope brake) has also made toprope climbing "socially acceptable", meaning that it can also be practiced without a climbing partner. Paraclimbing competitions are also mainly held in the top rope.

Paraclimbing

Paraclimbing refers to climbing for people with physical and mental disabilities. Depending on the type and severity of this impairment, athletes are assigned to different categories within which they measure their strength.

The first IFSC Paraclimbing World Championships took place in Arco (IT) in 2011. Since then, this discipline has become increasingly important and fascinates spectators from all over the world.

Speed climbing

In most respects, speed climbing probably stands out among the climbing disciplines. First and foremost, speed is the deciding factor in this discipline. The speed route is basically internationally standardized, making speed the only discipline in which world records can be set. The most important factors for success in speed climbing are speed and maximum strength, speed, maximum gripping and kicking precision and the ability to memorize the movements of the route precisely.

In addition to classic speed climbing on artificial holds, there are also some notable speed climbing ascents of a different kind on the rock. For example, Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell climbed the "Nose" on El Capitan (almost 1000 m) in record time (1 hour, 58 minutes) in 2018. Dani Arnold's speed record on the Grosse Zinne is also incredible: in 2019, the Swiss climbed the 550-metre-long Comici-Dimai route free solo in 46 minutes and 30 seconds.

Combinations

The combination format was developed for the 2020 Olympic Games (2021) and has already been used in several national and international championships. The individual disciplines of speed, then bouldering and finally lead are climbed, resulting in an overall score.

Previous observations have shown that the Olympic combination is a major challenge for competitive athletes, demanding everything from them both physically and mentally.

Alpine sport climbing

We are slowly moving into the more adventurous realms of climbing: Alpine sport climbing is a combination of alpine and sport climbing. This includes the following aspects: It involves multi-rope tours, whereby easy passages are preferably secured with mobile belay devices such as friends, wedges or webbing slings etc., while difficult passages are equipped with bolts.

In most cases, the bolts are drilled and placed from below. This is in line with the ethics of the great pioneers of this discipline and has one main consequence: difficult sections must be climbed free! Why? Quite simply: Imagine the first ascender trying to overcome a difficult passage. He has tried this passage dozens of times and still doesn't know whether it is climbable at all.

His main concern is to move on to the next good hold where he can build a self-protection - perhaps on a skyhook that he has only placed on a small corner. He sits in this belay, pulls the drill upwards from his belay partner and tries to set a bolt there, while hoping to keep enough balance so that he is not thrown out of the wall together with his self-belay and the drill and tears a long descent downwards. This means that the bolt can only be placed above the difficult section, which means that the crux has to be climbed free. Of course, it would be possible to abseil down in order to additionally secure the route, but this does not correspond to the ideology of alpine sport climbing.

Nowadays, however, you do find the odd climber who, for whatever reason, is rather unimpressed by tradition.

Mobile belay devices

Plaisir/multi-rope tours

If a route is longer than one rope length and belays have to be set up, it is referred to as a multi-pitch route. The length can vary. Even a length of 90 meters usually has to be climbed as a multi-rope route.

Nothing general can be said about the state of protection, as this always depends on the person setting up the route. Some routes are completely bolted, others leave more room for mobile intermediate protection. In any case, there is more to plan and consider than on a normal day in a sports climbing garden. For example, it is essential to have coordinated rope commands and checked the weather and route in advance. Descents/abseiling points on high walls also need to be found and extra time must be planned for this.

This also applies to plaisir tours, although these are a little less demanding in all respects: Plaisir tours have a moderate level of difficulty (up to about the 7th UIAA grade), are well secured with bolts and have a rather short and low-risk approach and descent. Simply enjoyable climbing.

Alpine climbing

In alpine climbing, the focus is on reaching the summit rather than overcoming the desired level of difficulty. Several rope lengths are strung together. There can be so many that you even have to bivouac on the wall. These are known as big walls.

There are often only a few bolts, which is why intermediate protection is used. Some alpine routes are absolutely clean, which means that not a single bolt is used for securing or orientation in the terrain. Here, the climbers themselves must have the necessary knowledge to read the route, place protection and build belays. The risk of a fall lies in poorly placed wedges, friends and pitons, as well as sand gauges that are too weak. These can break out in the event of a fall. Redundancy is possible by closely spacing the intermediate belays and, when climbing with two half ropes, by placing intermediate belays next to each other with one of the two ropes.

Due to the factors mentioned, such as route finding and belaying, alpine routes are often climbed a few degrees below the redpoint level in order to avoid risks.

Ice climbing is also a type of alpine climbing. Here, too, belaying is done by climbers themselves (ice screws) and climbing is generally very risky. Apart from that, it is in no way similar to rock climbing, because you know, ice and ice axes and all that ...

Alpine climbing on the Wilder Kaiser, Tyrol, photo: Simon Schöpf

Trad or clean climbing

In trad or clean climbing, mobile belays are attached to the rock and removed again once the route has been completed. This type of belaying was developed to avoid pitons. Yvon Chouinard, a pioneer in big wall climbing (and founder of the Patagonia brand), noticed back in the late 1950s that attaching pitons caused lasting damage to the rock. In order to avoid so-called "pin scars", he developed the first versions of clamping wedges that could be attached in cracks. Climbing devices have adapted to the times in terms of technology and safety standards, but they can look back on a long tradition. Today, mobile belay devices are so good that even beginners quickly take a liking to trad climbing.

Movement styles Free climbing

Free climbing means that only your own body is used to move vertically, but no artificial aids. This means that anyone who pulls on a rope to get over a point is no longer a free climber - at least not in this one attempt. Free-solo climbing is a special form of climbing in which you climb freely, but also alone - in other words, free climbing without a belayer or partner.

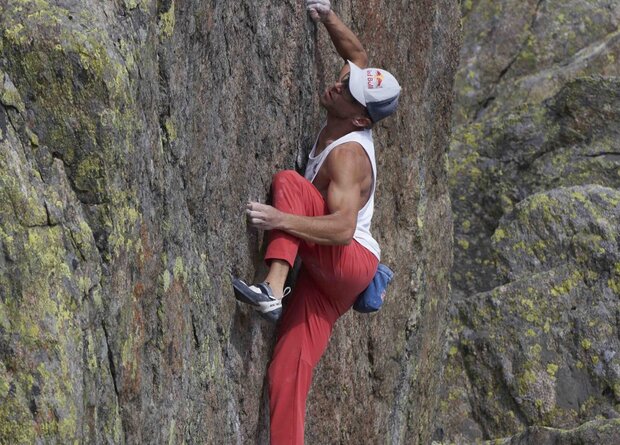

Free solo

If someone climbs a route free solo, they expose themselves to enormous danger, as they do without any kind of protection. Climbers on free solo tours have usually prepared themselves meticulously and bouldered out the routes precisely so that no more mistakes are possible - in theory at least.

Free solo climbers need an extremely strong mindset, the ability to concentrate fully on the here and now and a great deal of basic trust in their own strengths. And this is precisely where the appeal of the activity lies, according to "free soloists".

Since Alex Honnold's hit movie "Free Solo" at the latest, the discipline has become known beyond climbing circles, although it has to be said that the movie has distorted the reality of normal climbers, as only very few are that "crazy".

Free solo base climbing is considered a supplement to this, whereby the climber wears a base chute on their back so that they can pull the base chute in the event of a fall. However, the "rescue chute" option only makes sense if a certain jump height is reached. In the event of a fall in the first 10 meters, the canopy would probably have no effect.

Deep-water soloing is also more or less free solo climbing, whereby a fall into the water reduces the risk of injury. Some competitions are also organized in this discipline, such as the American Psicobloc Masters.

Redpoint

Redpoint climbing means climbing a route that has already been checked out up to the redpoint. It is irrelevant whether the route has already been climbed for the hundredth time or only for the second time.

However, if you are asked about the redpoint level, the answer should include the grade that can be achieved within 2 to 3 attempts. So if you regularly climb 7b and have scored an 8a once, your redpoint level is: 7b, not 8a.

Climbing with an overhang at the Arzbergklamm - testing your personal redpoint level, photo: Günter Durner

Pinkpoint

Exactly the same as above, only with pre-hung quickdraws. The term tends to be neglected in the community.

Brushpoint

Not yet a household name, but perhaps soon: Brushpoint is the new style from Alex Megos, who has probably run out of hard projects. In the "easy" Frankenjura classic "Father and Son" (8c), Megos brushes almost every hold he touches during the ascent. Funny - and not entirely serious, but definitely "level up"! Incredible performance, Alex!

Onsight

Onsight is the free ascent of a route on the first attempt and is probably the most honest form of ascent. With an onsight, you don't get any solutions, nor are there any quickdraws hanging in the wall. Strictly speaking, there should also be no tick marks on the rock. If your climbing buddy had told you last week that on a route on the third bolt you had to keep the ledge fully closed on the right and extend it twice on the left, and you scored the route on your first attempt today, it would no longer be an onsight, but "only" a flash.

Flash

Flash is the ascent of a route on the first attempt with the collection of information about the solution to the route. If you attempt an onsight and someone calls out to you from below that there is a hidden crimp that you might have missed, it would ultimately be a flash.

We have now reached the end of our vocabulary check, and hope on the one hand that it is complete, and on the other hand that it will help you to be even more "g'scheider" at the next climbing regulars' table.