Drinking coffee with the pink field hippo mouse

I regularly find myself wandering through magical worlds, hopping through Charlie's chocolate factory with the Oompa Loompas and drinking coffee with a little pink hippo with a red hat - until the three magical words "Martina, concentrate!" ring out.

Concentrating is a real challenge for me from time to time. While I'm climbing, I prefer to comment on the conversations of my climbing partners instead of focusing on the next move, and instead of doing one more pull-up, I laugh and let go one pull-up earlier. You don't have to be that dogged, do you?

Concentration - focus, focus!

I obviously struggle with this. But if you want to climb well, you should learn to concentrate. If you prefer to climb a boulder on the first attempt, you should learn that too. And if you like to save energy when checking out single moves, you should too (makes sense if you want to memorize the beta). It doesn't have much to do with doggedness.

For people like me, there are people like Madeleine Eppensteiner - herself a sports psychologist. She regularly trains with athletes on a mental level, mainly (but not exclusively) with climbers. And Madeleine knows one thing: focusing helps you enormously - both in training, in the project and in competition. BUT: It has to be learned. Madeleine gave me some tips on what I need to pay attention to and how I can learn it.

Theory on concentration and focus

There are four dimensions to how you can align your focus. To make the following theory a little easier to understand, imagine your focus as a spotlight that can direct its focal length on four levels depending on your requirements:

1. outside-wide

Your spotlight is directed into the surroundings, many things are illuminated, but nothing is really completely recognizable or too detailed. Your attention is not focused on your own person. You try to capture the situation as a whole, like a "panoramic image". Focusing at this level is often the case when you are in a new environment, such as a new hall/competition venue or a new area.

2. outside-narrow

The spotlight focuses on something in the environment, such as the route you are facing - or more specifically, the move you need to make next. In this state, there is only the route and you.

3. inside-out

Here you perceive your current state of mind. How am I feeling right now? Do I feel fit or limp? If I can answer these questions, I can create a positive mindset or do more exercises to activate myself. This is particularly important just before the start.

4. inside narrow

Your spotlight focuses on your breathing or your thoughts, for example. Here I can specifically counteract negative emotions. For example, if I'm totally insecure before I get on the plane, I talk to myself positively or think about positive consequences if I master the situation.

The right focus for the best possible concentration

Perhaps, like me, you are now looking for a ranking and trying to understand what is good and what is bad. Well, a positive or negative evaluation of these levels is not possible and also not necessary, because most situations are too complex to say that I only need level 1 or 2.... It is always more important to weigh up exactly what we are focusing on at any given moment. Sometimes it is important to focus on the heavy single train, other times it is more important to pay attention to possible dangers in the environment, such as falling rocks.

The requirements vary depending on the situation. The change usually happens quickly. Bouldering, for example: your perception switches between focusing on a few moves, the perception of external requirements such as timing in a competition and sensing whether you are recovered enough to make another attempt. You have to switch quickly here, but all sub-areas are important.

Concentration exercises: Learn to deal with distractions: Consciously build distractions into your training, for example loud music or someone talking loudly to you from behind. Work with self-instructions/talking to yourself: Verbally direct your attention to positive thoughts or to actions (doesn't even have to be spoken, it can just be on a mental level). Self-talk must be formulated positively - block out doubts and brooding ("Stay positive!") Focus on the next important thing - not the one after that. Ignore questions about yesterday and tomorrow: It's about the HERE and NOW. Don't evaluate situations subjectively (positively or negatively), but try to evaluate them neutrally. Mindfulness exercises have a positive effect on focusing, whether it's mindful walking (i.e. paying attention to every step), counting breaths, etc.

The sentence: "Just concentrate" - often said by trainers, teachers or others who try to teach you something - is counterproductive in this respect, because it lacks the information about what exactly I should concentrate on. And you also have to learn that you can't always concentrate - your ability to concentrate is limited, such as the length of a route ascent. After that, the "concentration bag" is used up for the time being (and you can go back to drinking coffee with the little pink hippo with the red hat). So don't be too hard on yourself.

And now a sentence that should act as the focus of this text:

CONCENTRATION CAN BE TRAINED!

You can learn to concentrate in different ways, develop strategies for doing so and quickly switch between them. The non-plus-ultra would of course be to live a concentrated lifestyle. Concentration can be practiced anytime and anywhere. This doesn't mean that we always have to be focused, but that we learn to consciously concentrate when we need to. And the better we can do it, the better we can apply it flexibly (incidentally, this applies to all our skills).

To do this, you should develop suitable routines, practise them in training and apply them in challenging situations.

I would like to thank sports psychologist Madeleine Eppensteiner for all this information. You can find out more about this and other sports psychology topics on Madeleine's website at www.climbingpsychology.com. A look at her website can have a very broadening effect.

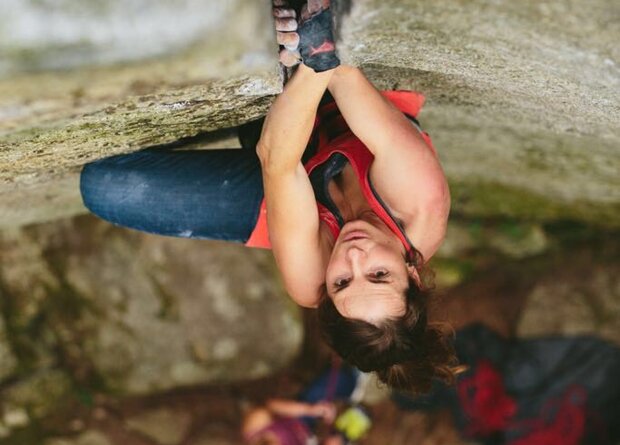

Madeleine Eppensteiner, sports psychologist, photo: Lena Drapella

Concentration for the competition

Two Austrian athletes who will be competing in the World Cup gave me their tips on how they prepare immediately before a competition:

Hannah Schubert:I don't have any particular rituals. If I'm in the isozone for a long time, I try to distract myself and not think too much about the competition. As my start approaches, I focus and make sure that I only have positive thoughts in my head. I think about previous successes, about competitions that went well. In this way, I motivate myself and encourage myself. "You know you can do it, you're in super good shape. Just do it like you did at the competition in Briancon".

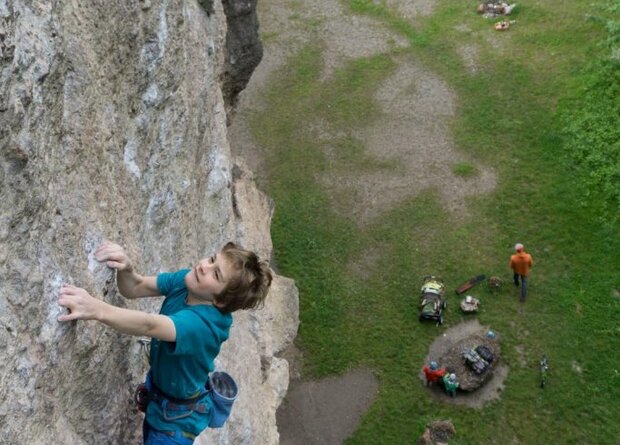

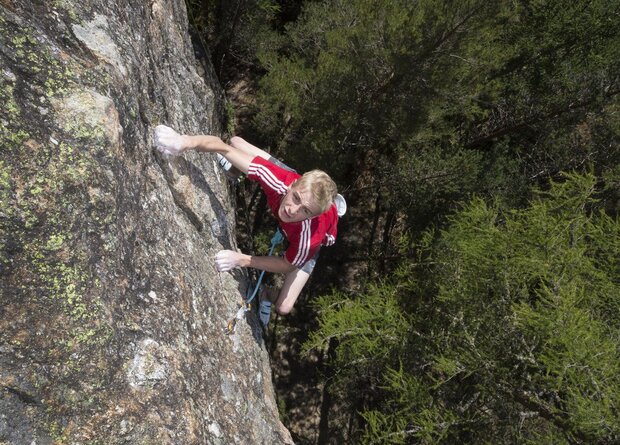

Hannah Schubert, photo: Ben Lepesant

Julia Fiser: Just before the start of a competition, I listen to motivating music and go through the moves in my head. Most of the time, the routes look really cool when I look at them and then I really look forward to climbing them. Just before I get on, I smile and say to myself "Do it like you did in training - then it'll work!" Apart from that, I don't get stuck on rituals or anything like that. There can always be changes during a competition, and if I can't perform a ritual for some reason, it stresses me out and I want to avoid that so that I can prepare for the route with as much freedom as possible.

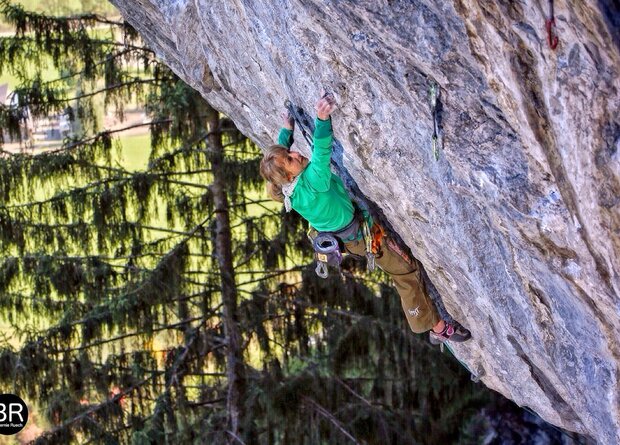

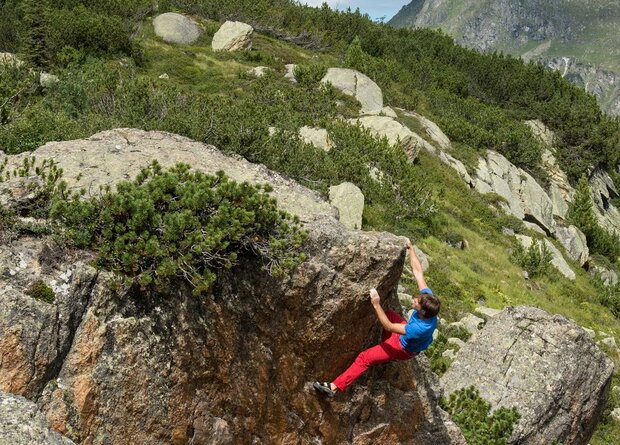

Julia Fiser